속도의 고고학_강덕봉의 근작들

현대적 상황에 천착한다. 속도가 극대화되면서, 즉 “떠나기도 전에 도착해 있는 상태”가 지배적으로 되면서 지리적 공간의 가치도 소멸해간다. 이런 상황에서 저항은 지리적(공간적) 거점을 확보하는 일이 아니라 차라리 속도를 변화시키거나 지속을 방해하는 일로 가능하다는 것이 비릴리오의 판단이다. 속도를 정치화할 필요가 있다는 것이다. 2)

이와 유사하게 강덕봉은 “기술의 속도가 가속화되어가는 과정을 추적하면서 예술의 저항적 형태를 탐구”(작업노트, 2015)한다. 그런데 이 일은 실제로 어떻게 가능한가? 즉 예술 실천을 통해 속도를 정치화하는 일은 어떻게 가능할까?

일단 우리는 대상-이미지를 분할, 해체하여 얻은 단편들을 일정한 규칙에 따라 재결합하는 식으로 근대적 ‘속도’와 공간의 ‘힘선들(force lines)’을 가시화했던 과거 미래파 예술가들-이를테면 보치오니(Umberto Boccioni), 발라(Giacomo Balla)-의 작업들을 떠올려볼 수 있다. 뒤샹(Marcel Duchamp)의 저 유명한 <계단을 내려오는 누드>(1912)를 연상해봄직도 하다. 실제로 강덕봉의 근작들은 단편들-PVC 파이프 조각들-을 이어 붙여 형태를 구축하는 식으로 속도와 운동의 감각을 창출한다는 점에서 미래파나 뒤샹의 선례를 상기시킨다. 하지만 강덕봉의 근작들은 단순히“속도와 힘선을 가시화하는” 수준을 넘어서 있는 것으로 보인다. 그것을 “미래파적인 작업”으로 규정하려는 순간에 시야에 들어오는 ‘독특한 요소들’이 존재하기 때문이다.

강덕봉의 작업노트를 살펴보면 여기에는 광학적 미디어(optical media)에 대한 관심이 유난히 두드러진다. “스피디하게 전개되는 영화의 한 장면을 캡처한 것과도 같은 나의 형상들” 또는 “다양한 크기의 파이프로 이루어진 나의 형상들은 빠른 속도에서 순간적으로 포착한 잔상의 다발들”(작업노트, 2015) 같은 서술들 말이다. 속도란 “움직이는 기계, 곧 모터 영화(moteur cinematographique)의 발명품“ 3)

이라는 비릴리오의 인식을 고려하면 속도에 천착하는 강덕봉이 영화에 주의를 돌리는 것은 어쩌면 당연한 일이다. 그런데 강덕봉의 근작들에서 영화. 정확히는 영화의 전사(前史)에 등장하는 다양한 광학 미디어들은 개념적으로 참조되기보다는 작업의 물질적 양상에 실질적으로 개입된 모양새다. 가령 <99:59:59:99>(2013)는 하나의 머리를 공유하는 세 개의 몸 다발들이 그 머리를 중심으로 빙빙 돌아가는 모습을 선보인다. 이렇게 몸-다발들이 어지럽게 빙빙 돌아가는 느낌을 선사하는 <99:59:59:99>는 물리학자 조제프 플라토(Joseph plateau)가 1832년에 선보인 어떤 기계의 형태를 닮았다. 플라토가 페나키스토스코프(Phénakistoscope)라고 명명한 이 기계는 원반 형태인데 그 원반 가장자리에 16개의 이미지가 있고 그 사이 사이에 같은 숫자의 슬릿(slit)이 있다. 관객이 거울 앞에 원반을 놓고 어느 한 슬릿에 눈을 대고 원반을 돌리면 댄서가 끝없이 빙글빙글 도는 모습을 볼 수 있다. 주지하다시피 페나키스토스코프는 광학적 환영을 기술적으로 구현하는 식으로 영화발명을 촉진한 여러 스트로보스코브 장치 가운데 하나다. 또 다른 사례도 있다. <일상이 된다는 것>(2017)에서 3차원 공간을 점유하고 한 점을 중심으로 빙빙 도는 상태에 있는 몸-다발들은 마레(Étienne-Jules Marey)의 3차원 조에트로프(zoetrope, 1837) 기계를 연상시킨다. 조에트로프는 ‘삶’을 뜻하는 ‘조에 ζωή’와 회전을 의미하는 ‘트로포스 τρόπος’가 결합된 단어로 굳이 번역하면 ’생명의 바퀴‘ 라 할 만한 것이다.

<99:59:59:99>나 <일상이 된다는 것>에서 보듯 강덕봉이 집중하는 형태는 둥근 원반, 또는 원통 형태들이다. 그가 자기 작업의 기본재료로 쓰는 PVC 파이프가 기본적으로 속이 빈 원통 형태임에 주목할 수도 있다. 그 파이프의 원통 형태는 마레의 광학 미디어, 연발사진총(fusil chronophotographique, 1881)을 연상시킨다. 연발사진총 촬영자는 장치를 어깨에 고정한 후 조준기로 표적을 겨냥하고 방아쇠를 당겨 사진을 찍었다-정확히는 “쐈다shoot”. 그러면 11개의 네거티브 필름이 담긴 원통이 30도 회전하고 다음 11개의 네거티브가 준비될 것이다.4)

장 뤽 고다르(Jean Luc Godard)는 “영화는 초당 24번의 진실이다!”라고 주장한 적이 있다. 그런데 우리의 눈이 영화적 운동의 외견상 연속성을 진실된 것으로 믿으려면 영사된 이미지는 충분히 빨리 깜빡여야 한다. 이것은 광학 미디어가 감각 생리학과 불가분의 관계임을 시사한다. 실제로 19세기의 미디어 기술은 생리적으로 지각 가능한 최소한의 차이보다 더 세밀하게 작동하는 기계를 추구했다. 그 과정에서 기술적 질문은 생리적 질문으로, 기계를 만드는 일은 인간의 감각을 측정하는 일로 전환했다. 5)

결국 광학 미디어는 “생리적으로 강요되는 환영”을 추구하고 있었던 셈이다. 여기서 중요한 것은 시각기관을 자극하는 빛과 그림자의 흔들림이었다. 다시 비릴리오를 인용하면 영화에서 “현실효과는 빛의 방출로 창출”되었고 “형태의 변화는 조명의 강도에 따라 생겨” 6)

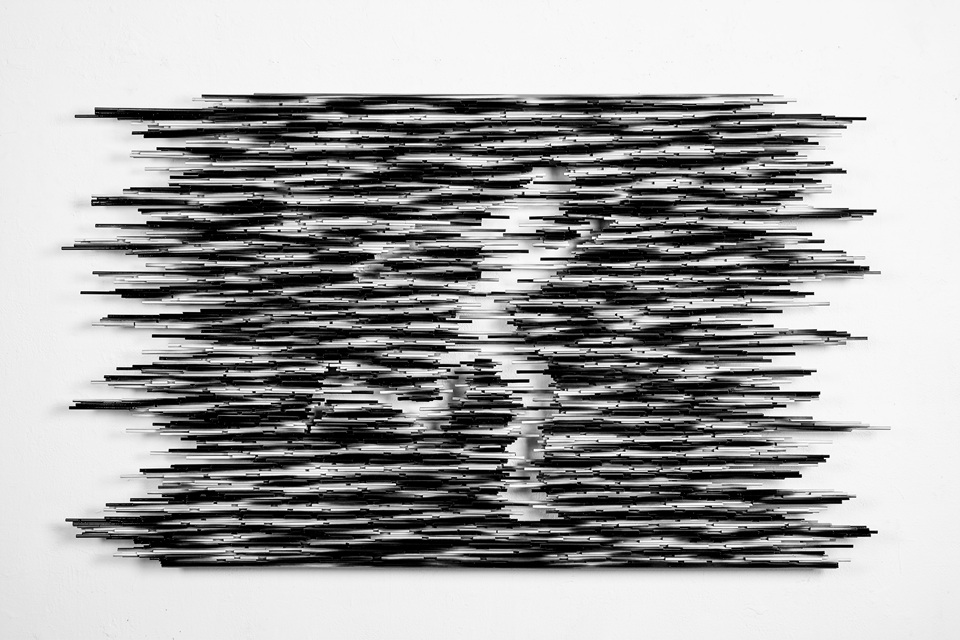

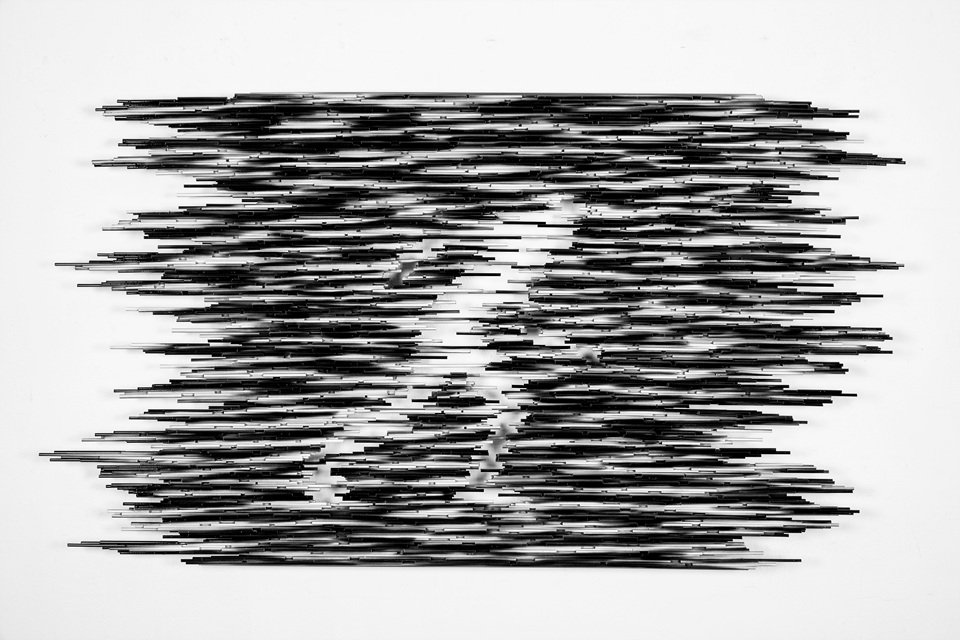

났다. 강덕봉의 <부유하는 공간> 연작(2015~2018)에서 네거티브 형태로 제시된 신체 이미지의 현실감, 운동감이 빛(과 그림자)의 효과인 것처럼 말이다. <부유하는 공간>들은 움직이는 빛의 비정형 세계를 연출한다. 이와 유사하게 강덕봉이 필름처럼 투명한 것들에 열중하는 현상에 주목할 수도 있겠다. <인식하는 신체>(2018)들에서 빛이 투과되는 투명한 표면들에 주목해야 한다는 것이다.

지금까지의 관찰에 따르면 강덕봉의 근작들은 옛 광학 미디어들로부터 조형요소들을 절취해 자기 작업의 요소들로 삼는다. 이것은 영화의 전사(前史)를 꽤 기이한 방식으로 재상연한다. 키틀러(Friedrich Kittler)는 “영화의 기술적 요소들이 단계적으로 아주 천천히 하나로 조합됐다”고 서술했다. 즉 기술미디어는 페나키스토스코프, 조에트로프, 연발사진총 따위의 성과들을 하나씩 조합하는 식으로 영화의 완성을 향해 나아갔다. “그것은 때때로 하나로 합심해서 뭉치고 때때로 자연스레 결정화하는 아상블라주의 형태(chain of assemblage)로 나타났다”는 것이다. 7)

흥미로운 것은 강덕봉이 그것들을 영화의 익숙한 방식으로 조합하지 않고 자신만의 매우 독특한 조각 어법으로 조합한다는 점이다. 강덕봉은 <정지된 일상>(2018)에서 마침내 소리 이미지마저 덧붙이는 식으로 “무성영화로부터 유성영화로의 발전”을 비틀어버렸다. 그런 의미에서 강덕봉의 근작들은 영화라는 상상계에 균열을 가하는 작업으로 평가할 수 있다. 다시 “속도란 움직이는 기계, 곧 모터 영화의 발명품“이라는 비릴리오의 발언을 떠올려보면 강덕봉은 속도가 발생한 기원 시점에 개입하여 속도의 크기와 벡터, 효과를 변형 중이라고 말할 수도 있겠다. 그런 의미에서 강덕봉의 근작들을 ‘속도의 고고학’으로 명명하면 어떨까? 아무튼 나는 이 기묘한 아상블라주의 묘한 반짝임에 끌리는데 이러한 끌림은 영화에 적응한 내 몸틀이 반응한 것인지, 아니면 조각언어에 친숙한 내 인식틀이 반응한 것인지 오리무중이다.

2) 이재원, 「속도와 유목민-우리는 저항할 수 있는가?」, 위의 책, p.289.

3) Paul Virilio, 김경온 역, 『소멸의 미학-시간과 속도의 여행』(1989), 연세대학교출판부, 2004, p.38.

4) Friedrich Kittler, 윤원화 역, 『광학적 미디어: 1999년 베를린 강의』(2002), 현실문화, 2012, p.245.

5) 위의 책, p.227.

6) Paul Virilio, 김경온 역, 『소멸의 미학-시간과 속도의 여행』, p.103.

7) Friedrich Kittler, 윤원화 역, 『광학적 미디어: 1999년 베를린 강의』, p.236.

Archaeology of Speed-Duck Bong Kang’s Recent Works

Duck Bong Kang’s recent works begin “by attempting to capture the absurd desire we have for speed”. Capturing the desire for speed translates into “capturing a stream of processes that have flowed away fast and been overlooked” (Work note, 2015). His intent is to produce artistic creations of what Paul Virilio called ‘the politics of speed’. Virilio’s speed theory named ‘Dromologie’ focused on modern situations where the strategic value of the non-place of speed had supplanted that of space.1) As the speed maximizes, i.e. “you arrive even before you leave”, the value of space gets lost. Virilio believed that we can resist in this environment not by securing a location(space), but by changing the speed or disrupting its continuation. In other words, he argued for a need to politicize the speed.2) Similarly Kang “tracks and studies how the pace of technology has been accelerated to study the artistic form of resistance” (Work Note 2015). But, how can this be possible in the real world? In other words, how can artistic activities politicize the speed?

First, we can start by going back to futurist artists – Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla- who dissected and dismantled objects-images, and reassembled resultant pieces following certain rules to visualize the force lines of modern ‘speed’ and space. Or you may want to recollect the well-known ‘Nude Descending a Staircase’(1912) by Marcel Duchamp. Indeed, Kang’s recent works are reminiscent of those of futurist artists and Duchamp as he groups and glues together pieces- the pieces of PVC pipes-to create shapes, thereby the senses of speed and movement. But Kang’s works are “just more than visualizing the speed and force lines”. It is because when you are about to define his works as the one of a futurist artist, you will see something unique.

Kang’s keen interest optical media is highlighted in his work note, in especially his statements such as “it looks like that my works capture a scene of a fast-paced movie.”

or “ the works made of the pipes of various sizes are a cluster of images captured instantaneously at a fast pace” (Work note 2015). It is no wonder that Kang has turned his eyes to movies as he delves into the speed considering Virilio’s belief that the speed is “a creation of a moving machine, i.e., moteur cinematographique”3) . And Kang’s recent works show that diverse optical devices in the prehistory of cinema have physically become part of his works, instead of being conceptually referenced. For example, ‘99:59:59:99’(2013) shows a cluster of three bodies sharing one head are spinning around the head. This work resembles the shape of a machine created by a physicist Joseph Plateau in 1832. The machine was named Phénakistoscope by Plateau and is shaped as a disk in which there are 16 images along the edge of the disk. There is also the same number of slits between the images. So, through the splits, people can see dancers spinning constantly if they place the disk in front of a mirror and spins it. Phénakistoscope provided a technical creation of optional illusions and was one of many stroboscope devices that promoted the invention of movies. There are other examples as well. In ‘Becoming daily life’(2017), the artist presents a cluster of bodies that keep on spinning around a certain point in three-dimensional space. This reminds us of the three-dimensional zoetrope machine(1837) created by Étienne-Jules Marey. Zoetrope is a term coined by combining zoe(ζωή) meaning ‘life’ and tropos(τρόπος) meaning rotation and can be translated into ‘the wheel of life’.

As ‘99:59:59:99’ and ‘Becoming daily life’ indicate, the shapes that Kang is focused on is a round disk or cylinder. This brings one’s attention to what he usually uses for his works- PVC pipes, i.e. empty cylinders. The shape of pipes reminds us of the fusil chronophotographique (1881) created by Marey. The photographer mounts the device on his/her shoulder, aims at an object and pulls a trigger to take-or shoot, to be more accurate – a picture. Then, a cylinder containing 11 negative films are rotated 30 degrees and next 11 negative films get ready.4)

Jean Luc Godard once declared “The movies are truth twenty-four times a second.” But for our eyes to believe that the seeming continuation of cinematic movements is true, the projected images should blink fast enough. This indicates that optical media is inextricably linked with esthesio-physiology. Indeed, in the 19th century, the media technology sought machines that function more precisely than what can be physiologically perceived. In the process, technological questions became physiological ones and making machines turned into measuring human senses.5) In the end, what the optical media sought was ‘forced physiological illusion.” What is important here is shaking lights and shadows that stimulate visual organs. Again, Virilio said “in the movies, the reality effect is the response of light emission” and “change in a shape is caused by the intensity of lighting.”6) This is in line with Kang’s ‘Floating Spaces’ series (2015-2018) in which the reality and movement of physical images presented in negative forms are the effect of light (and shadow). The ‘Floating Spaces’ series present an atypical world of moving lights. Similarly, this can bring our attention to Kang’s focus on transparent objects like film. In ‘Body that we are aware of’ (2018), one needs to focus on transparent surface through which light penetrates.

My observations indicate that Kang’s recent works take formative elements from old optical media and use them for his artworks. This approach provides a very unusual replay of the prehistory of cinema. Friedrich Kittler said “the technological elements of movies have been gradually and slowly combined and formed into one.” In other words, technological media has moved toward the creation of a movie as we know it by combining various achievements such as phénakistoscope, zoetrope and fusil chronophotographique. “They sometimes have been merged and combined together and have naturally evolved into a chain of assemblage”.7) What is interesting is that Kang doesn’t combine and merge them in a familiar way as movies do, but he combines and merges them using his own unique language of sculpture. In ‘Suspended daily life’(2018), Kang went as far as to add sound image, giving a twist to the perceived “cinematic evolution from silent ones to sound ones”. In this regard, Kang’s recent works can be seen as disrupting the existing mechanism of cinematic imagination. Given Virillio’s remarks that “the speed is an invention of a moving machine, i.e. moteur cinematographique”, it is fair to say that Kang steps in at a point when speed is created and transforms the size, vector and effect of the speed. In this vein, how about naming his recent works as ‘archaeology of speed’? For some reasons, I’m drawn to the unique sparkle of this unusual assemblage. But, I’m clueless whether this is the response of my bodily framework that is accustomed to movies or the response of my perceptual framework that is familiar with the language of sculpture.

1) ‘Speed and Politics- from politics of space to politics of time’ (1977) written by Paul Virilio & translated by Jae Won Lee, Greenbee, 2004, p2432) ‘Speed and Nomad- Can we resist?’, Jaewon Lee, the above book, p289

3) ‘Esthetics of extinction-Travel of time and speed’ (1989) written by Paul Virilio & translated by Gyeongon Kim, Yeonse University Press, 2004, p38

4) ‘Optical Media:1999 lecture series in Berlin’ (2002) written by Friedrich Kittler & translated by Won Hwa Yoon, Hyunsil Book, 2012, p245

5) The above book, p227

6) ‘Esthetics of extinction-Travel of time and speed’ written by Paul Virilio & translated by Gyeongon Kim, p103

7) ‘Optical Media:1999 lecture series in Berlin’ written by Friedrich Kittler & translated by Won Hwa Yoon, p236